Always Understand WHY Before Making any Swing Changes

How is it that even in the 21st century golfers try to ‘do this or do that’ without any concern for whether the human body is actually capable of unwinding from the Gordian knot (picture below) that the golf backswing typically places it in? Amazingly, no one seems to care whether the body, the brain and the motor control system have any specific strategies capable of returning the golf club to the ball. No one asks which joints are required to be moved, which muscles move them, and how it is all managed.

Amazingly, no one seems to care whether the body, the brain and the motor control system have any specific strategies capable of returning the golf club to the ball. No one asks which joints are required to be moved, which muscles move them, and how it is all managed.

Moreover, the ‘do this, or that’ suggestions are typically made as a set of opposites. For instance, “Your shaft is too laid off at the top, you need to be more across the line” or “Your clubface is open at the top, it should be more neutral”. Sometimes ‘match-ups’ are recommended. What are they? They are a make-up opportunity for a faulty backswing position through using some compensatory downswing movement.

Can the human body do everything that’s required of it consistently? After all, it was not designed for golf but merely for the chief role of our ancient ancestors – to ‘hunt and gather’!

Can you simply make practically any recommended motion in the backswing and even in the early downswing and hope to deliver the club to a precise location on the ground consistently? Keeping in mind that the downswing requires a specific ground-up sequence and takes place in less than 1/3rd of a second for all skill-levels of golfers.

Let’s first find out how golf movements have evolved over time. Secondly let’s understand which movements are currently in fashion and why. Finally, let’s discover when the unbending and untwisting of many joints from their top of backswing positions is easy, and when it is not-so-easy to manage.

Some Golf Swing History

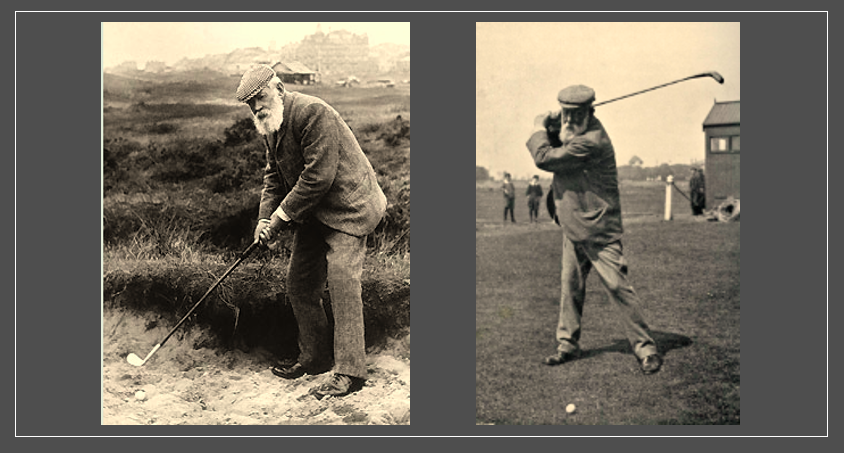

A few decades ago, a golf swing looked like that seen in the pictures (from around the 1870s) below. They are of Old Tom Morris (who lived from 1821 to 1908 and is often referred to as the father of golf).

Golfers simply bent over to hold onto a fairly short golf club, and then had to raise their arms (and thus the trail side of the body) considerably, to make a long-enough backswing to get some speed into the downswing. No science to it!

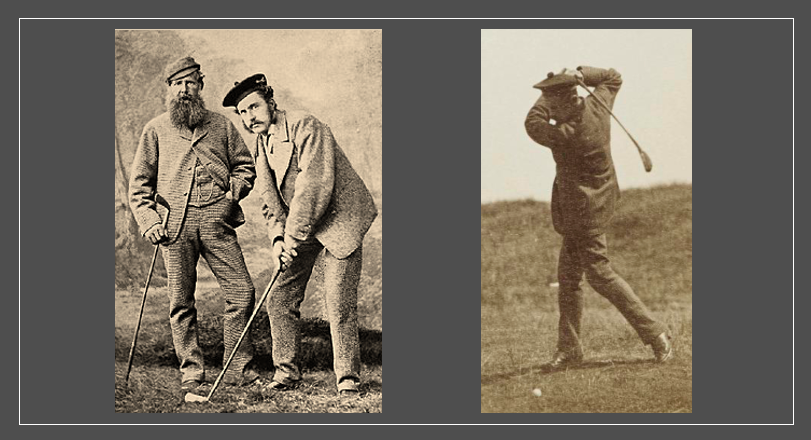

With time, and mainly with experience, came the ideas for more body motion (even from Old to Young Tom Morris, see pictures of the son below). Ideas began to include a perfect ‘path’ for the arms and club to travel on, that were observed to deliver longer, straighter ball-flight more often than not.

Golfers added bits and pieces of ‘knowledge’ to those they passed on information to, primarily from their own experiences playing the sport. Those who performed well were typically those whose swings were the most reported and copied, a case in point being the popularity of Jack Nicklaus’ book ‘Golf My Way’. Swings over the years were thus similar at any given time and changed to reflect the thinking of the times, usually quite subjectively.

In more recent years, the golf-swing has been considerably researched, but mostly through observational studies. Such studies do not necessarily tell us whether a particular position or movement or applied force in the backswing or early downswing actually causes some specific near-impact or impact condition.

In the absence of any true experimental research on the golf swing that involves an actual intervention of something different, all current scientific knowledge of golf is a collection of what golfers, mainly highly skilled golfers, do. Which, often,

- Is not a best-case scenario

- Merely represents current thinking on the swing i.e. swing ‘fashions’. That is a result of all the pros learning the same things ‘incestuously’ from the same teachers who get their information from the same sources

- Is very varying even between the best golfers (picture below)

Moreover, golf swing research is termed biomechanics research, but it usually studies the ‘mechanics’ aspect far more than the ‘bio’ one. The tools of biomechanics (motion capture, force plates etc.) produce measurable results that are then interpreted from a mechanical perspective, without much consideration of the ‘bio’ aspects of: anatomy (design of bodily structures), neuro-anatomy (design of the central nervous system) and motor control (how the brain controls movement).

With the increasing use of force plates (to measure foot-ground interactions), it has been noted that lateral, up-and-down and rotary movements in the downswings of skilled golfers are associated with specific directions of forces. So now, all golfers, including already skilled golfers, are asked to push into the ground this way and that to create more force for greater club speed and this results in even more movement.

With the advent of the need-for-speed as well as some bits of observational research, movements have become even more complex and, in fact, positively wild. Golfers are told to make a shift-turn-and-shift-turn type motion going back and through, with centering by the top of the backswing, and some ‘unweighting and weighting’ (up and down movements), including a drop down-and-towards-target motion in the downswing.

Sadly, not every golf-swing topic or question has been, or can be, researched. As a result, modern-day golf swing practices and instruction are a combination of new information and, where there are gaps, traditional lore. And the results speak for themselves. All skill levels of golfers, including the long drivers with their excessive motions (pictured above), and Tour professionals, have inconsistencies when they can least afford them, especially under pressure.

So what should golfers do in the absence of adequate scientific knowledge? Every golfer and golf coach needs to ask and understand the WHY. In other words, a golfer should ask WHY should I make a particular swing change and “If I make a swing change, which joints will be moved, by which muscles, and how will the brain control it all”?

If someone has a club face that is open at the top but is required to be neutral, they should ask WHY does that matter? If someone believes greater club speed comes from a swing that moves many body parts in multiple directions, they need to ask WHY is that so? If someone wishes to have a mainly arms swing, once again, they need to ask WHY?

Understand the WHY when using only Club-Related Terminology

How often are you told that your club is laid-off or across the line or open or closed at the top? Or perhaps that your shaft is not on plane? Or that your clubface is open or closed at impact? And that the club’s position needs to be modified?

Understand that it is always muscles and muscle groups that cause specific joints to move, and those joints then move the club in a specific manner. The entire movement is controlled by nerves (motor neurons) in the brain and spinal cord that must use specific common strategies (e.g. gravity or the need for dynamic balance) to deliver the club to the ground at impact.

So it is important (for someone – coach or golfer) to understand all the joints that are moved (intentionally or unintentionally) in the performance of a particular task. Are all those joints, by virtue of their design-constraints, capable of the movements they must undo in the temporally-constrained downswing?

Additionally, as the human motor control system is well-designed for target-oriented movements, it will try its best to ‘somehow’ deliver the club to the ground. What needs to be understood is whether the ‘somehow’ is adequate for the purpose of a fast swing that must arrive at the ball with a square face and from a slightly inside path.

Here’s an example of what I mean. In this video https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-pdHQOH1k-s (minutes 2:04 to 2:56), expert commentator Brandel Chamblee describes club and individual joint positions that are good (left) or not so good (right, in the picture below). However, a club position at the top or a trail elbow position halfway down, is the result of many body movements and they all need to be taken into consideration when trying to understand the value of a particular swing.

Only then can one begin to analyze what will happen from the top of the backswing with and without conscious thought. Without conscious thought, the motor control system will find the simplest path to the ball – the reason why over-the-top and early extension are so common.

The situation does not become easier with conscious interference (e.g. some variety of ‘keep the butt cheeks against a wall’ or ‘keep your back to target and drop your lead leg’ etc.). Why? If one movement is sought to be deliberately controlled, some other body part will unconsciously move differently from expected (see: Coordination-variability and kinematics of misses versus swishes of basketball free throws Mullineaux & Uhl, 2010).

Understand the WHY for Axial Movements

Axial motions for the purpose of this post refer to those of the legs, torso and head – all body parts closer to the midline of the body. They are the most complex to undo from the top of the backswing – even for a putt or chip shot!

One example of a mainly-axial backswing movement requires the torso to rotate as much as possible with minimal pelvic rotation. Another is when the lead leg, hip, waist and shoulder all have to be lower than their counterparts on the trail side at the top. Yet another is away-from-target weight shift.

The first example means that individual vertebrae have been twisted by small spinal-support muscles (see the wrinkles in the shirt of the famous golfer pictured below), but they cannot be untwisted in precise order during the very short downswing time. So the motor control system simply tries to drop the torso down and forward.

The second example requires a common strategy as there is no time for separate commands to the trail side to drop down and the lead side to lift up. And this gets complicated when towards-target weight shift must be factored in as well.

It is quite simple to make most set-up positions. It is also fairly easy to make most suggested backswing movements (provided golfers have the required flexibility for some of the more excessive ones). Both are fairly simple because there is enough time to make them.

However, all intentional axial downswing movements are difficult because:

- The trunk/torso (involving mainly the thoracic and lumbar spinal regions) has a very different nerve supply from that of the arms and legs. In the trunk muscles, one nerve will control multiple muscle fibers, and motion is typically slow and rudimentary. And yet we expect highly sophisticated torso movements in the 300 milliseconds or less that the golf downswing lasts.

- Innervation to trunk and shoulder muscles is sparse (less nerves go to that region, see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zKA8iaxfEww, minute 30:42 to 31:38).

The legs and arms do have better innervation but their movements become complicated because both feet are attached to the ground and both hands are attached to the club (forming closed kinetic chains within which both limbs become connected and have more complex movement capability).

- The more muscles or muscle groups involved, the more problematic the downswing becomes. For each muscle that must contract to move a specific joint, there is nerve conduction velocity and electromechanical delay to account for. The time frame for each of which could be 30 ms or more. [See: Cortical control of erector spinae muscles during arm abduction in humans (Kuppuswamy et al. 2008), Electromechanical delay in human skeletal muscle under concentric and eccentric contractions (Cavanagh & Komi, 1979) and Characterization of electromechanical delay based on a biophysical multi-scale skeletal muscle model (Schmid et al. 2019)].

- The golfer is trying to move several large, heavy parts of the body that are difficult to move – in a precise, well-timed downswing sequence!

- When a golfer is told to push forward through one foot and backwards through the other, or down then up through the lead leg or any other pushing activity through the feet to effect some extra amount of ground reaction force, and thus, supposedly body motion, what really happens?

The ground is merely a passive resistance against which muscles can contract. The brain (primary motor cortex with modifications from the basal ganglia and cerebellum) is already designed to code a movement for force, direction, extent and speed (see: https://nba.uth.tmc.edu/neuroscience/m/s3/chapter03.html and https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zKA8iaxfEww, minutes 10:37 to 13:53). What the eyes see and the proprioceptors in the joints perceive, the brain codes for. Interference is non-ideal.

As one tries to add an intentional push into the ground, changing the existing program in the brain, the positions or movements of other involved joints can change, often in undesirable ways. Try running fast while trying to push each foot back in turn (to increase forward propulsion) and see how that works and feels!

- World famous biomechanist Stuart McGill has disseminated his years-long golf research in a video entitled The New Science of Golf (see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vznEOX-BAvs ). He has stated that golfers are ‘elastic athletes’ who strategically store and recover elastic energy. All that’s needed to create greater force and power (along with stiffer joints) is a pulsing of involved body muscles. His research shows that the trail gluteus maximus pulses just before impact and the trail external oblique at impact.

Which begs the question – why, then, subject the body to large ranges of difficult-to-perform-consistently motion as well as often, to injury. Simply allow the key muscles of force production to stretch during the backswing, then shorten quickly and without conscious thought, close to impact.

What, Then, is the Solution?

The solution is to use mainly the large, powerful muscles of the shoulders, the shoulder girdles (scapulae) and torso along with trail elbow extensors. In other words, use a backswing that practically reverses current thinking – minimal axial movements with maximal arms motion!

This is achieved through the backswing stretch and downswing shortening of several trail side muscles – all created only through a wide and deep arms motion and not through any twisting and turning of body parts such as head, legs or pelvis.

Specifically, the movement involves the shoulder movers – latissimus dorsi (LD), teres major, pectoralis major (PM), and, through interdigitation (interlocking of muscle fibers), the torso mover – external oblique (EO), and the shoulder blade mover – serratus anterior.

If such a swing additionally has minimal protraction of the trail shoulder blade close to impact, it can also use the strong trail elbow extensor – triceps brachii – to produce considerably more, and more appropriately directed, force than mere wrist movers.

The lead side torso rotator – internal oblique, and perhaps some shoulder-blade retractors may also be involved in downswing force production.

Finally, in such a swing (The Minimalist Golf Swing), the large muscles would all contract forcefully against the solid foundation of the legs which do not move and provide a stable base for said muscles to contract forcefully against.

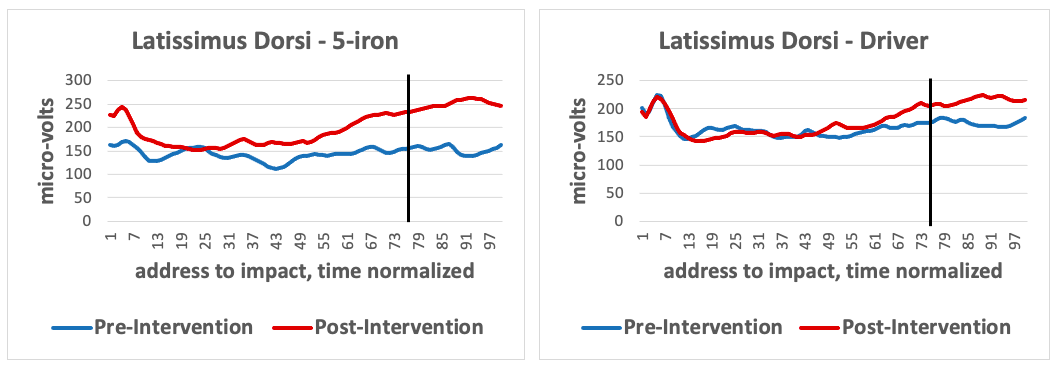

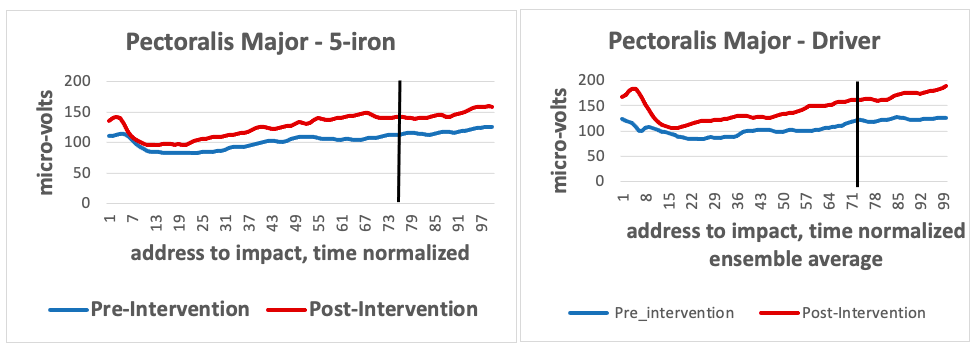

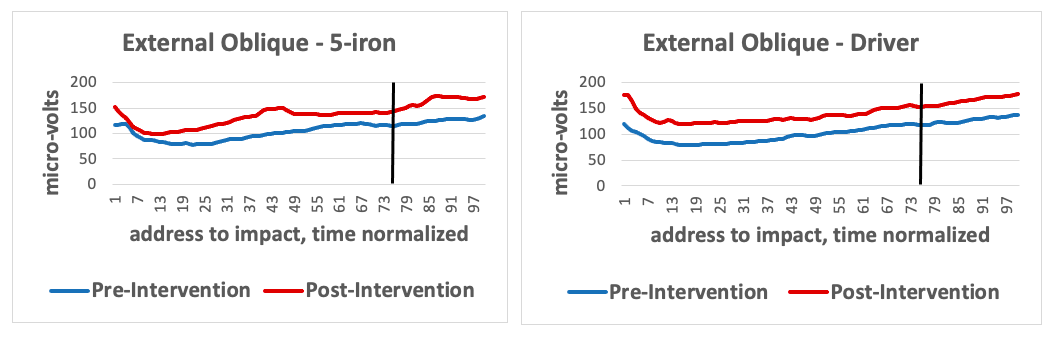

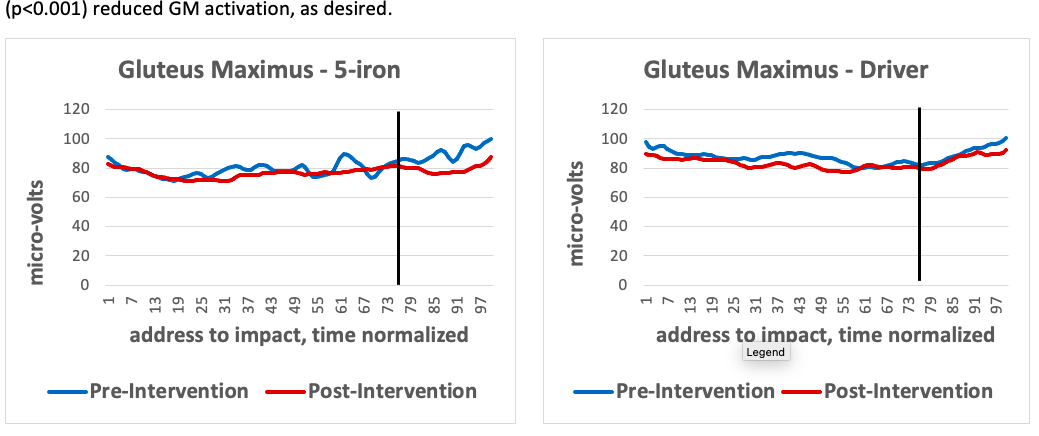

The graphs below indicate the muscle activation levels of five trail side muscles as seen through an electromyography study that compared the activity level with golfers’ existing swings and The Minimalist Golf Swing:

- 12 right handed golfers

- Age range 18 – 73

- Handicap range 7.6 – 18

- Single session, during which their existing swing’s EMG patterns were analyzed, then their Minimalist Golf Swing EMG patterns were measured after a 15 minutes training session

- Participants hit 5 shots each, pre- and post-, with their own 5 iron and driver clubs

- Five right side muscles were tested for electrical activity indicative of muscle force production

- All graphs are (ensemble) averages of the 12 right-handed golfers x 5 swings per golfer per club (5-iron and driver). All muscles are right-side muscles.

Downswing is the last ¼ of the movement, indicated by vertical line.

The LD, PM, EO, Gluteus Maximus (GM) a hip extensor and external rotator, and Biceps Femoris (BF) a hamstring muscle that extends the hip and can flex the knee, were studied.

There was higher average activation levels for the 12 participants in the LD, PM and EO with The Minimalist Golf Swing. There was not much muscle activation either pre- or post- for the trail Gluteus Maximus. The BF graphs are not included as there were inconsistencies even in participants’ existing swings for the 5 iron and the driver.

The well-researched Minimalist Golf Swing is the only swing designed for far greater consistency of results, the same or better speed as with a traditional swing, a more inside path with almost zero chance of a leftward miss (for a right-handed golfer), a slight push that is easily corrected, and less injury risk. Get in touch to learn more.