27th March, 2024

[Brought to you from the website – www.YourGolfGuru.com – that was recently nominated as one of California’s Top 10 blogs by Feedspot]

Padraig Harrington – The ‘Bees Knees’

This article was meant to be written. By a series of synchronicities or simple serendipity, if you will.

First, it just happened that while passing the media center at the Hoag Classic, Padraig Harrington was being interviewed. Then he was practicing at the driving range (in shorts) which was a great opportunity to see his lead (left) knee in a brace and then record his swing. After that, he was a compelling winner of the 2024 Hoag Classic. And finally, Annie Zuurveen of golfargus.com happened to have taken a picture of the interview and sent it on.

Why is Padraig Harrington the ‘bees knees’ in this story? What’s not for him to be the bees knees (‘an excellent or much-liked person’)? He has intelligence (listen to his many interviews), charm (that appealing Irish lilt!) and wit (always speaks with a touch of humor). And finally, this bees knees has issues with his knees – or at least his lead (left) knee.

Harrington as well as several other players were all asked, “What have you and your swing coaches done to keep your swing tuned in for better performance and less injury risk as you age?” His verbatim response, “You know I don’t know if we do less injury risk,” he chuckled, “I think we’ve pushed the limits a little bit too much but you know the way I kind of look at it – I work in the gym, I work with a physio to keep the injuries at bay, and I work with my coach to get the max out of my golf swing. I prefer to play well for the next two years, and then you know, be injured and gone. You know I’m at that stage in my career. So I’ll take a risk with my body and I certainly push my body to the limit but I hope that my gym work and stretching and physio work keeps me from getting injured.”

“So what are the swing things you do to go to the max? Is it distance you’re chasing?” To which Padraig replied, “You know still working on generally you know what anybody should be doing there’s a lot of basics in the game but I think as regards the speed element there’s probably two parts that you know we’re all working a bit more on – getting the ground forces working on being in position to use that the ground – our feet, our legs yeah, and I think the second thing is – I do it often…I literally try and swing fast every day I play. So I mightn’t do a full speed program, but you know when I’m out on the golf course and I’m not playing a competition, and when I’m warming up, I’ll hit a number shots in that warm up that I try and go to my max. The more often I can try and mentally go to my speed max, the better the speed is.” (see pictures below with him warming up with fast swings – OUCH! Excessive knee bend – valgus position – with raised foot in backswing and resulting foot slam-down, compression and excessive straightening – extension – in downswing)

It was alarming indeed to hear from such a talented golfer that he believes he can push himself ‘to the max’ and then be ‘gone’ in perhaps two years. Many on the PGA Tour Champions who were also interviewed – David Duval, Boo Weekley and Greg Chamlers amongst others – also have the belief that ‘working out’ is the panacea for all swing-related injuries.

In actual fact, it could be two days or two decades before the injury worsens enough to require drastic interventions.

Golf injuries are typically a result of making thousands of swings over time, and are referred to as overuse injuries. One 2013 systematic review paper ‘The effectiveness of exercise interventions to prevent sports injuries: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials’ reported on 25 research studies (on a variety of sports) that looked at 26,610 athletes with 3464 injuries. The review found that the risk ratio for overuse injuries from sport after a multiple exposure (combination of exercises including stretching, proprioception, strength-training etc.) style of exercise could be almost halved (47.3%).

So what about when risk is not mitigated through exercise? There are simply too many delicate tissues in human joints (ligaments, tendons, cartilage, bursae etc.) and too many forces and torques, positions and movements that cause injury, to make a blanket claim that exercise is the perfect preventive measure for all injuries.

Moreover, the tissue of concern could already be so damaged that all it would need would be a ‘straw that broke the camel’s back’ – known in medical terms as an ‘inciting event’! In a cadaver dissection class, some of my fellow classmates who were medical students cut around the tendons and ligaments outside one cadaver’s knee cap (patella) and we had our first amazed look at the mere thread that was all that remained of that cadaver’s anterior cruciate ligament (ACL)!

Finally, and most importantly, the reason that neither flexibility nor strength exercises alone suffice is because for many golfers the ranges their golf swing puts their joints through far exceeds their body’s natural capabilities.

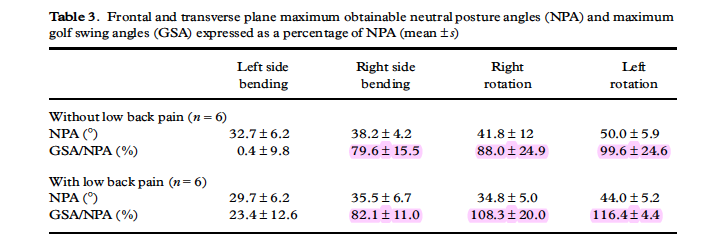

To better understand this concept read Lindsay and Horton’s 2002 research ‘Comparison of spine motion in elite golfers with and without low back pain’. Even though not about the knee joint, the same concept applies. The paper’s Table 3. (below) shows that golfers with low back pain have, on average, 116.4% of lumbar spine left rotation range of motion during their driver swings (compared to what they can produce when standing upright i.e. in ‘neutral posture angle’.

From video alone it is not possible to know which joints and which specific tissue Harrington might have pain or injury in. However it was obvious from the brace he wore that he had knee issues (confirmed from a year-old story in Irish Mirror.

A seminal review paper discusses possible mechanisms for knee injury, “The lead knee is more vulnerable to damage during the golf swing, according to many studies including that of Baker et al. (2017). The main injury-causing movements and loads include rapid knee extension when the knee is flexed between zero and 30˚ (angle between vertical femur and bent tibia); internal tibial rotation, strong compression of the tibiofemoral (TF) joint because of quadriceps femoris (anterior thigh) muscle activity, and large external ground reaction forces (GRF) acting on the knee (Baker et al., 2017).”

Another recent study (‘Lower Limb Biomechanics during the Golf Downswing in Individuals with and without a History of Knee Joint Injury’, 2023), suggests, based on its findings, that golfers who have had knee injury should reduce hip flexion and ankle abduction (toe out) as well as the entire range of motion for ankle abduction and adduction as other joints are also involved in knee injury.

We can see that Harrington has many of the dangerous movements mentioned above.

The fact of the matter is that while ‘using the ground’ is essential (just as using resistance against which to do any work is essential to all human activity), the method by which it is used in golf is not ideal and very easy to simplify.

The idea is to have a very stable lower body and allow the core, shoulder girdle and shoulder muscles to fire against that resistance, rather than move the legs and expect their muscles to produce force for the downswing. As the above referenced paper states, “When there was no knee joint injury, the player’s hitting strategy in the transverse plane was identified as being more stable with less ROM.”

So, Doctor of Golf (the ‘white coat’ is presented to the winner of the Hoag Classic because the Hoag Hospital is the involved charity) let’s get your anatomy and sports injury-causation grades up a bit, to add to your knowledge of all things golf!