What are ‘Anatomical Disconnects’? Why do they Matter?

23rd May, 2024/revised 16th August 2024.

To swing a golf club effectively, all body parts should be aligned by the “top of the downswing” (as defined by YourGolfGuru). This enables the arms to deliver the club to the ball in the best possible way, consistently. When the early alignment of some body part is complex to achieve, the golfer has one or more ‘anatomical disconnects’ – a phrase coined by YourGolfGuru.

While the downswing is typically referred to as the swing phase that extends from the top of the backswing to impact, the YourGolfGuru phraseology is slightly different:

• Top of Backswing – the point when the clubhead has reached its furthest backward motion (same as the traditional definition).

• Top of Downswing – the moment when the trail shoulder is level with the lead shoulder during the club’s movement towards the ball from the top (YourGolfGuru definition)

• Transition – the phase between the top of the backswing and the top of the downswing (considered by YourGolfGuru as a phase of ‘undoing the unnecessary’)

Top of Downswing as seen amongst the pros

YourGolfGuru’s desired Top of Downswing position

See how quickly the motion goes to Top of Downswing in the pictures below of top of backswing and top of downswing.

Top of the Downswing – the earlier the better

The earlier in the downswing the trail should is level-with, or slightly lower than, the lead, the more time a golfer has to accelerate the club into the ball, without having to wait for some body parts to ‘fall in line’.

How can an early Top of Downswing be Achieved?

By avoiding Anatomical Disconnects.

During the downswing, especially in the latter or acceleration phase when the club is accelerating towards the ball, it is crucial to make the most of your body’s ability to speed up, given the specific body and arm positions you need for impact. [read conclusion section of: Demircan et al (2012). Muscle Force Transmission to Operational Space Accelerations During Elite Golf Swings]

Since the entire downswing takes only about 1/3 of a second, for all skill levels of golfers, it is important to reach the acceleration phase of the downswing quickly. This gives you more time to build up club speed. If any part of your body needs extra time/motion to get into the position you need during the acceleration phase, it can disrupt and delay the swing’s smooth motion toward the target.

‘Anatomical disconnects’ are body parts that need some extra movement to align with their late downswing-to-impact direction of movement.

Anatomical disconnects include positions of the head, torso, legs, shoulders, elbows and wrists. The more disconnects a person has, the more complex the swing.

The further that specific body parts move away from their Top of Downswing position, the more disconnected those parts become. A few examples of anatomical disconnects are:

1. Trail arm raised (abducted) by more than 90° (see below). This involves raising the trail clavicle and thus another set of muscles requiring to be controlled during the downswing!

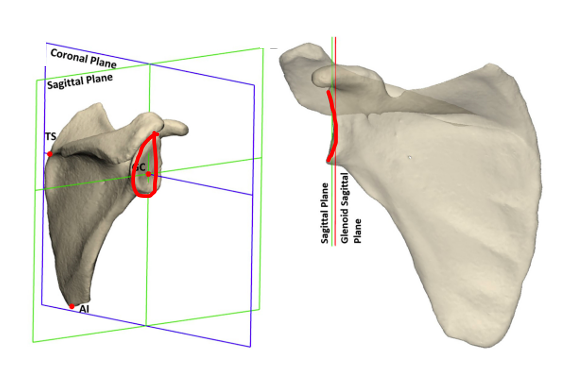

2. Trail scapula’s glenoid fossa facing the sky (see below). Yet another set of muscles required to lower it, and that much more work for the motor control system! It is important for this body part to be lowered so that it can present the trail shoulder in the correct position for the downswing.

3. Trail torso higher than lead. What sense does it make when it is lower at both address and impact (see address, top and impact pictures below)?

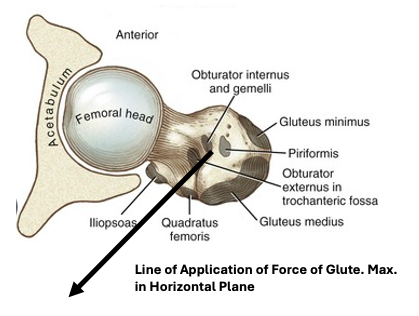

4. Trail hip higher than lead. Did you know the gluteus maximus (GM) muscle applies 71% of its force to unrotate the pelvis in the horizontal plane? In a typical golf swing the trail hip is at an angle and the two hips need to be level for maximal GM force application. And that happens so late with the traditional swing (see below)!

Information on force generation capabilities of the gluteus maximus muscle in the Nerdy Notes section below)

5. Trail knee kicked in and bent. No good player has that position by the Top of the Downswing, so why have it at the top of the backswing?

6. Weight shifted towards trail side. (These days they’re telling leading players to shift weight back but then have it centered by the top of the backswing – why bother, in that case?)

7. Torso and pelvis rotated to face away from target excessively (pelvis rotation is always unnecessary and never required)

When many body parts require to be ‘reconnected’ before the acceleration phase of the downswing can begin, it takes more time to reach the Top of Backswing position and often, with faster players, is achieved through a mish-mash of movements all happening at once, resulting in a clubshaft not always well-positioned for an inside, shallow approach.

What are important Top of Downswing positions to achieve?

1. The trail scapula’s glenoid fossa should be horizontal

2. The trail shoulder should be level with, or slightly lower than, lead shoulder

2. The trail shoulder should be level with, or slightly lower than, lead shoulder

3. The trail hip should be level with the lead hip

3. The trail hip should be level with the lead hip

4. The trail shoulder should be behind the lead shoulder

4. The trail shoulder should be behind the lead shoulder

5. The trail thigh should not yet have rotated forwards (see picture above).

What is the best way to avoid or reduce Anatomical Disconnects?

Avoid all the above-mentioned anatomical disconnects by maintaining head, torso and leg stillness in the backswing and moving the arms correctly to position both themselves, and the body, as needed.

If done correctly, the top of backswing position is barely different from the Top of Downswing one, and ‘transition’ (a phase of ‘undoing the unnecessary’) is negligible.

As you can see, these are all unique, never-considered-before, highly scientific concepts. For a biomechanical/anatomical assessment of YOUR ANATOMICAL DISCONNECTS, get in touch with YourGolfGuru.

Also, if you believe that it is important not to try to use downswing compensations to make up for backswing faults, get in touch.

You do not need to get rid of all your anatomical disconnects. Even reducing just a few can dramatically improve performance and reduces injury risk. Additionally, most can be removed through just a few set-up and backswing adjustments.

Use the contact form on this website to book your first session to success now.

NERDY NOTES 1.

It is important to note the findings of one research article (Zhang & Shan, 2014, Where do golf driver swings go wrong? Factors influencing driver swing consistency) in which the authors define ‘transition’ as the short time period between the backswing and the downswing.

Their definition for transition time was time spent in the transition phase. “The transition phase is more commonly recognized by practitioners than by biomechanists. It is loosely understood to be the time period between backswing and downswing. In this paper, we specifically define it to be the time period between the end of deceleration of backswing and the start of acceleration of downswing for the leading hand (left for all of our subjects). Based on this definition, the acceleration of the leading hand during transition is approximately 0 m/s2 or the hand speed < 0.3 m/s.” The average transition time was reported to be 0.021s for their population of 22 male golfers of average handicap 12.3 with a standard deviation of 10.1 (a rather wide range of skill levels!).

Their research findings showed that the “Transition phase is essential for a powerful swing” and that X-Factor could be maximized with a short pause. It should be noted that the researchers found that a short pause at the top allows X-Factor to be increased. They then relied on others’ research (!!) to state that X-Factor increase is known to increase club speed. However, not all studies have found a correlation between X-Factor and club speed (see Han et al. 2013).

While it may be true that greater transition time will permit a greater X-Factor Stretch (which is what the researchers are actually referring to), the excess time is mainly required to undo all the anatomical disconnects in the first place!

NERDY NOTES 2

One fabulous paper on the hip joint is titled Kinesiology of the Hip: A Focus on Muscular Actions (Neumann, 2010). The author, with reference to the biggest towards-target rotator of the hip – the gluteus maximus states, “Maximal-effort activation would theoretically generate 71% of its total force within the horizontal plane,”

So, the trail hip needs to be in (ideally), or get into, as soon as possible, the horizontal plane to generate as much of its force in rotating it as soon as possible! Hence the need for a transition phase with the traditional swing, as described in NERDY NOTES 1. Transition allows the raised trail hip to get level with the lead one so that horizontal plane trail hip rotation may begin for the greater X-factor Stretch the authors referenced in NERDY NOTES 1 desire.