Dynamic Balance – A Fresh Look

[Note: This post is best appreciated through the discarding of a ‘confirmation bias’ which leads humans to “Search for, interpret, focus on, and remember information in a way that confirms one’s preconceptions”]

BIG PICTURE:

What is dynamic balance and why does it need a fresh look?

According to the wisdom of a group of the top minds in golf instruction in the 1970s, dynamic balance requires “Having the appropriate weight shift during golf swing while maintaining body control”.

That definition was a part of a paper by Dr. Gary Wiren titled ‘Ball Flight Laws, Principles and Preferences’, in which dynamic balance was one of 14 ‘principles of higher order’ and thus very important. The paper also stated that ‘hanging back’ during the downswing could cause directional and distance issues.

Despite considerable subsequent research (see in the DETAILS section below), no one has fully explained exactly how weight shift (more appropriately referred to as center of mass or COM shift) can be ‘appropriate’, how it might be observed/measured, and how it causes directional and distance issues.

The most common-sense definition for dynamic balance (more in the DETAILS section below) is to have the upper body/torso stacked directly above the lower body/legs at impact, so that the body-part that delivers the arms and club to a stationary ball on the ground is centered on top of its ‘base’. After all, at address, the two body parts are fairly well stacked. Moreover, as the ball does not move during a golfer’s backswing, why wouldn’t they be stacked at impact?

If the two parts do not stack up, the arms and hands have to make compensations like ‘flipping’, or the pelvis has to slide or tilt to somehow get the arms to reach over to deliver the club to the ball.

Imagine how the person in picture on the left might have more inconsistencies that the person in the picture on the right, especially if he cannot flip or slide at the right moment in the downswing.

Every time the motor control system has to make compensatory downswing movements there is a chance of inconsistency, of both direction and distance, even amongst the best golfers in the world, especially under pressure.

Even a great golfer like Rory McIlroy, who has the modern backward torso lean-back, has inconsistencies. Mainly because when his timing is messed up, he too has to make compensations to deliver the club to the ball from his unstacked position.

The pictures above are screen shots from a very recent youtube video. So, the picture on the right was not quite at impact.

In the picture on the right you can see that his hands are already on top of the ball but his clubhead still needs to get to the ball. What will his arms, given his unstacked body, have to do to get the club to reach the ball (orange line)? He probably cannot jump up much further, so he will probably have to do something last-minute with his arms and hands. Or rotate his pelvis more. And he does!

As his pelvis rotates more, his forearms roll over (the tell-tale sign of forearm roll-over is that his trail elbow is facing down the line instead of behind him). Can you imagine how that movement is a weakness for him as it could easily lead to clubface control issues when his timing gets messed up, say under pressure?

TRY THIS to better understand the importance of stacking the top of the body over the bottom (and thus reducing the need for complex downswing torso motions):

Get to the top of your backswing and then, without moving the body, legs or head at all, simply straighten your arms and hands. From a ‘typical’ top of backswing position, the arms are only at about waist high when they straighten, so that the body must make considerable sideways and rotational movement to get stacked and that might get messed up under various conditions.

When a swing remains mainly fairly stacked from address to impact, the straightened arms drop almost all the way to the ball – leaving limited opportunities for body misalignments. The golf instructors of old said it best when they asked golfers to ‘swing in a barrel’ or keep the upper and lower bodies stacked on top of one another.

Golfers, start 2024 by making a non-compensatory golf swing with proven results for both performance improvement and injury risk reduction!

The Minimalist Golf Swing (MGS) improves performance by using only those positions and muscles that actually deliver required speed to the arms and club and no more. It also reduces injury risk because the moment arms of many forces get reduced from stacked shoulders and pelvis.

SOME NERDY DETAILS

I Several researchers have studied dynamic balance in the golf swing. Earlier studies actually measured static balance (during stationary standing) which is not the same as dynamic balance.

More recent papers have looked at dynamic balance (by comparing the location of the movement of the golfer’s center of mass (COM) to that of the movement of the net center of pressure (of both feet). None of the papers have explained why dynamic balance matters except in a vague way by stating that a well-coordinated movement leads to an efficient and more stable swing.

I too define dynamic balance as a center of mass issue, and like to compare the upper-body COM with the lower-body COM. As already mentioned, if the two are fairly stacked at impact, the body will make less downswing ‘compensations’ to deliver the arms and club to the ball. A ‘compensation’ here is anything intentional a golfer has to do in the downswing to ensure the club reaches the ball.

Some well-known research papers on balance in golf:

- Sell, T. C., Tsai, Y. S., Smoliga, J. M., Myers, J. B., & Lephart, S. M. (2007). Strength, flexibility, and balance characteristics of highly proficient golfers.

- Choi, A., Kang, T. G., & Mun, J. H. (2016). Biomechanical evaluation of dynamic balance control ability during golf swing.

- Choi, A., Sim, T., & Mun, J. H. (2016). Improved determination of dynamic balance using the centre of mass and centre of pressure inclination variables in a complete golf swing cycle.

These and other papers on dynamic balance show that it has not been well-defined for the specific purpose of the golf swing, nor its benefits well-understood.

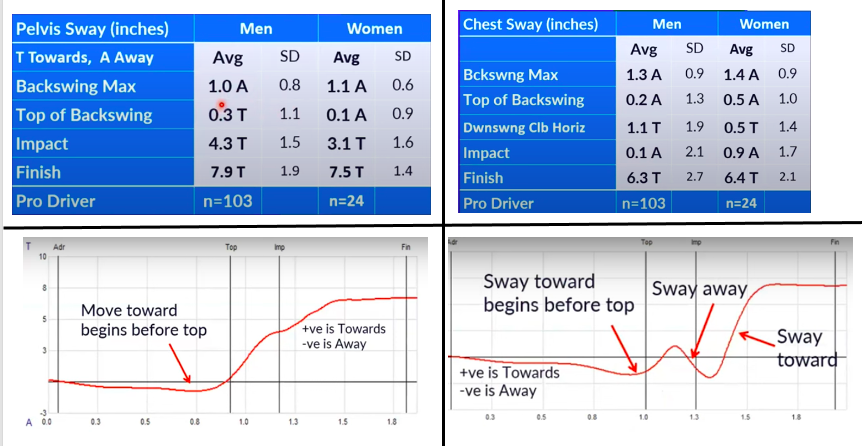

II One measurement that comes close to explaining dynamic balance has been put forward by Dr. Phil Cheetham of Sportsbox AI, who has developed an app. that converts 2D video into 3D, and measures many useful aspects of the golf swing. The measure of interest here is referred to as ‘sway gap’. It indicates how much the pelvis and chest move, relative to one another, in a side-to-side direction during the swing.

The sway gap (watch this video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JYU8F-JpvGU) is measured as the distance between a vertical line from the middle of the shoulders and a vertical line from the middle of the hips (see picture below).

What sense does it make for the chest to be hanging so far behind the pelvis at impact? The picture (below) shows the typical pattern seen in the movements of 103 male and 24 female professional golfers.

The pros tend to move the pelvis away from target (A) and then, starting from just before the top of the backswing, towards target (see picture below), with a slight stall at impact. They also move the chest away from target in the backswing, and then, before the top, towards target. However, after the top, the chest moves towards target and finally away from target until well after impact. What a mismatch! And what justification is there for it?

It does not matter that the pros have a large ‘sway gap’ at impact – they have the instincts and years of practice to correct for a mismatched upper and lower body by last-minute arms and hands movements or excessive pelvic motions. Usually. Under pressure they too have inconsistencies caused by the mismatch between the legs and pelvis on the one end, and the arms and torso on the other.

The entire concept of compensating for non-ideal positions at the top of the backswing through downswing ‘match-ups’ is preposterous. It is akin to taking beta-blockers for a heart condition, and then further medication for the side-effects such as asthma or higher blood sugar levels that result!

The best solutions are found by reverse engineering the golf swing from the requirements of club positions at impact. It is a far more reliable procedure than studying the pros, and trying to get into the same positions they do.

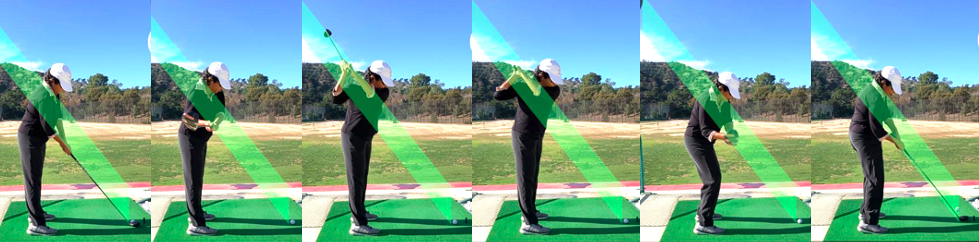

III And finally, a stacked lower and upper body go a long way towards preventing early extension, helping the arms stay on plane, and producing, without volition, excellent vertical forces.

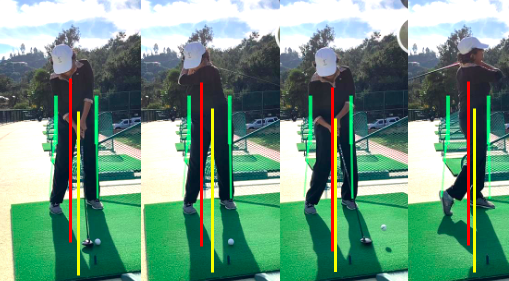

The pictures below were taken using a beta-test version of the app. XView, that golf instructor Mickey Osugi is involved in the delivery of. It shows the stacked body and the resulting lack of early extension, the on-plane club motion, and the effortless push-up for great verticals.

All merely from correct body-positioning at set-up, and no body (i.e. head, thorax, legs) movements during the backswing. Followed by a zero-thoughts downswing.

A very different sway gap pattern results from a fairly stacked body:

No thoughts of early extension ever needed:

Effortlessly on-plane:

Effortless, natural vertical thrust at impact:

Don’t let 2024 be groundhog day, golfers!

Switch to a compensation-free swing and…play your best golf, always.